Barolo wine

Barolo, also known as “the king of wines”, is one of Italy’s most noble wines. It is made from 100% Nebbiolo, in the hills of Langhe, near the town of Alba.

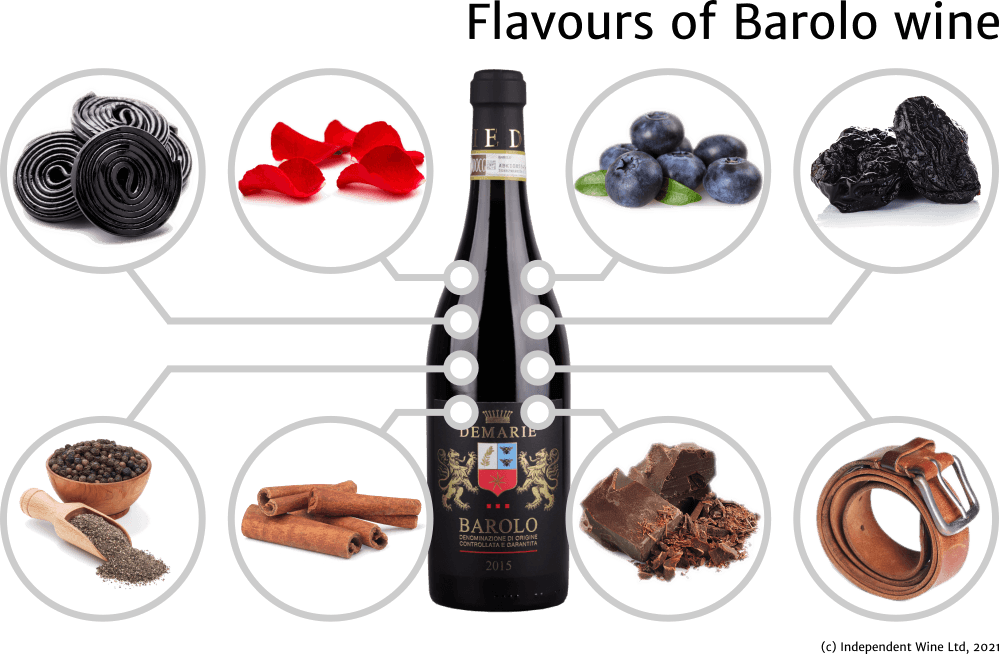

Barolo is praised for its complex and powerful flavour of dried flowers (rose and violet), dried red fruit (strawberry and raspberry), liquorice, tar and earth. Thanks to the long ageing process, it develops notes of spices (black pepper, cinnamon and juniper berry), rich dark chocolate, espresso, leather and sweet tobacco.

The Nebbiolo grape is notoriously rich in tannins: natural antioxidants, which create Barolo’s powerful flavour and austere mouthfeel. The wine benefits from long ageing, as tannins develop even more refined and sophisticated nuances over time.

It is advisable to keep Barolo for at least 5 years after harvest before opening it. A fine Barolo will continue to improve for decades.

If you’re wondering when the best vintages for Barolo are, 2010, 2013, 2015 and 2016 are considered the best years. As for vintages to be careful with, 2011, 2012 and 2014 were challenging.

Useful Links

Table of contents

- Where is Barolo produced?

- Key Barolo DOCG wine rules

- Barolo wine: Information card

- The aromas and flavours of Barolo

- Communes and cru vineyards in Barolo DOCG

- The Nebbiolo grape

- How Barolo wine is made

- The best and the most challenging Barolo vintages (in plain language).

- Frequently Asked Questions

- References

Where is Barolo produced?

The Barolo DOCG area stretches over the steep Langhe hills, rising as high as 500-550 metres, on the right bank of the Tanaro river. It sits near the town of Alba, 40km south-east of Turin.

The wine can only be made from grapes grown around 11 comunes (municipalities), which are shown on the below map of Barolo DOCG.

The Barolo area measures 9km across – from Cherasco (pronounced “Kerasco”) on the west to the eastern edge of Grinzane Cavour. From north to south, it spans 11km from Verduno in the north to Simone Scaletta’s vineyard on the southern edge of Monforte d’Alba.

The medieval villages of Barolo, Castiglione Falletto, Serralunga d’Alba, Monforte d’Alba and La Morra are responsible for the majority of production and are considered the most important areas.

The other six comunes – Grinzane Cavour, Diano d’Alba, Novello, Cerasco, Verduno, and Roddi – are less productive, but are home to number of award-winning wineries.

Wine buyer’s tip: If you are just starting your Barolo journey, wine from La Morra and Barolo are considered more approachable. They tend to be fruitier and softer. Meanwhile, experienced Barolo connoisseurs may prefer the more austere and powerful versions from Monforte d’Alba, Serralunga d’Alba and Castiglione Fallletto. These typically require more ageing, so patience is key.

Barolo from each commune has its own unique taste and character. This is because of the differences in soil type, the presence of natural springs, and the altitude of the hills. For a quick comparison, we’ll look at some of the Barolo wines in our collection:

- Demarie Barolo comes from the village of Santa Maria in the commune of La Morra. This wine is elegant and perfumed, with plush fruit flavours and a velvety texture.

- ForteMasso Barolo comes from the Castelletto cru in Monforte d’Alba. The most tannic Barolo in this selection, it is powerful, deep, and austere with the longest ageing potential.

- Francone Barolo is a blend of grapes grown in the Bricco Chiesa cru in La Morra (elegant, soft and perfumed) and Ravera cru in Monforte d’Alba (powerful, tannic).

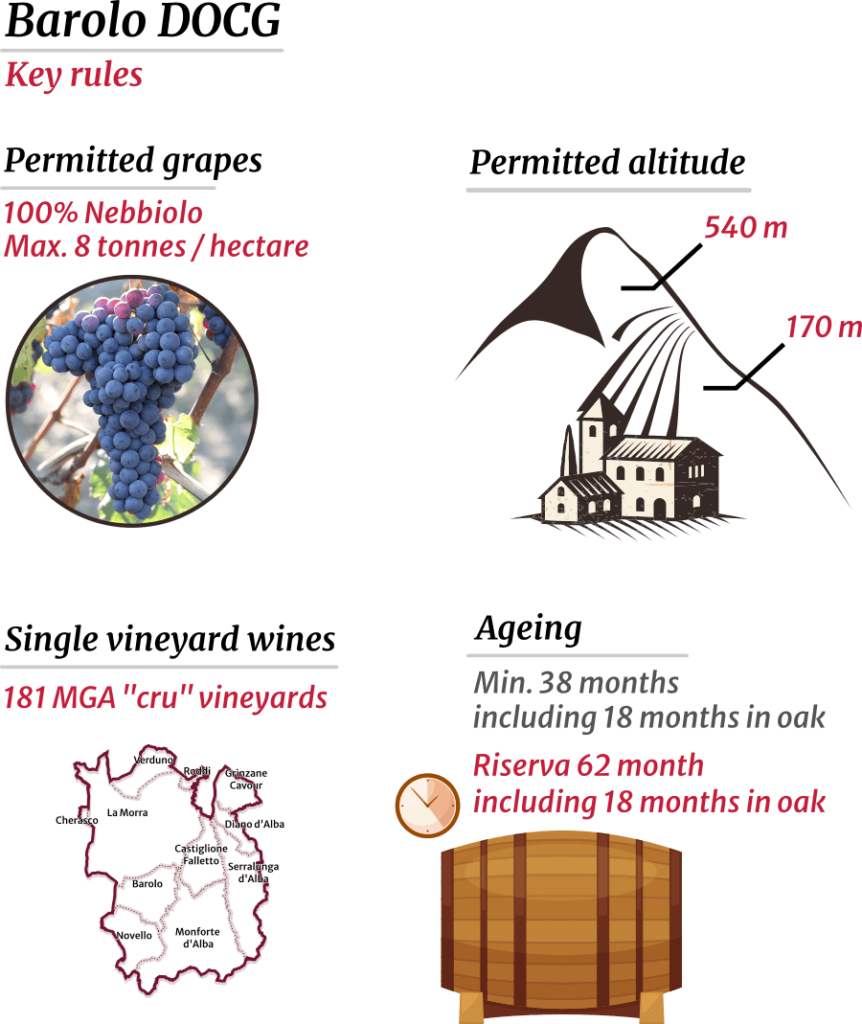

Key Barolo DOCG wine rules

The rules for growing, harvesting, ageing and bottling Barolo are defined in a statute called “Disciplinare di produzione”. It is often referred to as ‘the Barolo wine law’.

By understanding these rules – among the most stringent in Italy – one can see why Barolo is such a formidable wine.

Single vineyard (cru) Barolo

Wines crafted from grapes grown in a single vineyard (vigna) offer notes and flavours specific to their place of origin (the ‘terroir’).

Wine buyer’s tip. As a rule, if a winery has a single-vineyard Barolo in their range, this is their most premium wine.

Not all vineyards (vigna) can feature on the label. In the 1970s, the consorzio made a thorough analysis, and selected 181 vineyards across Barolo DOCG that were historically known to produce excellent wines. They are officially called menzioni geografiche aggiuntive (additional geographic mentions) or MGA.

Only if all grapes comes from a particular MGA vineyard, its name can be mentioned in addition to the word Barolo on the label. For example: Barolo Ravera DOCG. Unofficially, MGAs are known as the ‘cru’ vineyards of Barolo.

Here’s a collection of award-winning Barolos released by the Broccardo winery. Each of them is from a different cru, and show particular nuances of flavour.

Wine buyer’s tip. It’s not possible to say that one cru is better than the other: it’s a matter of personal taste. It’s the explorer’s joy to try Barolos from various cru vineyards, and find the one that resonates.

Barolo rules: grape quality

Barolo can only be made from 100% Nebbiolo grape. For the winemaker, the quality of the grape will define the quality of the wine. Only if the grape is perfect, the winemaker will be able to produce excellent wine. That’s why the quality of Barolo starts in the vineyard.

Fabrizio Francone, an award-winning third-generation winemaker, explains:

“The quality of great Barolo is born in the vineyards – we can’t add quality in the cellar. With winemaking and ageing we try to preserve the characteristics given by the terroir. We have to work really hard to preserve the full quality of the grape.”

Rules related to vineyard altitude and orientation

To protect the high quality – and high status – of Barolo wine, the disciplinare permits planting Nebbiolo only at altitudes of 170-540 metres. The most valuable vineyards are located mid-slope, and face either south-east, south, or south-west.

Such restrictions ensure that the grape has the best chance of ripening – and as a result, will produce better wine. If planted too low (e.g. on the valley floor), or too high, the grape may not receive enough light and warmth from the sun.

Barolo winemakers know that the best Nebbiolo comes from parcels where the spring snow melts first. Such sunny parcels are called sorì or bricco. Bricco is the term used specifically for plots on the upper part of the hill.

You will notice that many menzioni geagraphiche aggiuntive are in fact bricco vineyards. Examples include Bricco San Pietro (Monforte), Bricco Manzoni and Bricco Rocca (La Morra). These are just a few: there are many others.

Rules related to maximum permitted harvest

The disciplinare caps how many grapes can be harvested. This pushes the vine-grower to select only the best grapes, and ultimately produce better wine.

The general Barolo DOCG rule caps the maximum harvest at 8 tonnes of grapes per hectare. This translates into about seven thousand 75 cl bottles. For single-vineyard Barolo from a recognised cru (MGA) vineyard, the permitted maximum is even less: 7.2 tonnes per hectare.

To put things into perspective: if a winery wanted to release Langhe Nebbiolo DOC, it would be permitted to harvest 10 tonnes of grapes per hectare. In wine regions dedicated to mass-produced wines, this level goes up to 13–16 tonnes of per hectare.

The 8 / 7.2 tonne limit is among the most stringent in Italy, and protects Barolo’s overall quality.

Wine buyers tip: research which vineyard Barolo wine comes from. All reputable wineries will mention the comune their vineyard is located in, and its orientation.

Barolo rules: where Barolo can be produced

Grapes for Barolo wine can only be grown in the 11 comunes mentioned above. As a rule, Barolo must be produced within the area of Barolo DOCG.

However, there is an exception. If an organisation had been producing Barolo outside of the DOCG area before 1966, it may continue doing so. One example is Fratelli Martini Secondo Luigi S.p.A. located 15 km outside of the DOCG boundaries. It produces large volumes of inexpensive Barolo – often found in supermarkets.

Wine buyer’s tip. Small, family-owned wineries within Barolo DOCG craft some of the best examples of Barolo. Families take a long-term view and keep a high level of quality for every vintage. This protects their reputation. In bad years, they may chose not to release Barolo – and either declassify it as Nebbiolo Langhe DOC or sell the grapes off. Avoid Barolo that’s suspiciously cheap.

Barolo rules: ageing requirements

Barolo has one of the toughest ageing requirements in Italy. Even the “standard” Barolo must be aged for a minimum of 38 months, spending at least 18 months in barrels made from oak or chestnut.

Barolo Riserva has to be aged in the cellar for 62 months, including at least 18 months in oak, before release.

This is an extraordinary length of time. However, it is required to soften the powerful tannins of the Nebbiolo grape, thus creating the unique and desirable flavour of Barolo.

Wine buyer’s tip. The ageing time of Barolo is surpassed by Brunello di Montalcino, another great wine of Italy: it must be aged for at least 4 years. Sicily’s iconic fortified wine, Marsala Vergine is aged for 5 years or more. In contrast, Amarone della Valpolicella is aged for “only” 2 years.

Barolo wine: Information card

| Designation of origin | Barolo DOCG (Denominazione di Origine Controllata e Garantita) DOC since 1966, DOCG since 1980 |

| Location | Piedmont (Piemonte), Italy |

| Climate | Warm continental climate |

| Consortium | Consorzio di Tutela Barolo Barbaresco Alba Langhe e Dogliani http://www.langhevini.it/ |

| Styles and permitted grapes | Barolo: 100% Nebbiolo Barolo Riserva: 100% Nebbiolo |

| Rules | Barolo and Barolo Riserva, without additional geographic name: – maximum harvest 8 tonnes/ha – minimum alcohol content 12.5% Single-vineyard (“vigna”) Barolo and Barolo Riserva, with additional geographic mention (MGA) and vineyard name, followed by its toponym or traditional name: – maximum harvest 7.2 tonnes/ha – minimum alcohol content 13% Ageing, from 1 November after harvest: – Barolo: minimum 38 months, of which 18 months in oak; – Barolo Riserva: minimum 62 months, of which 18 months in oak; Earliest release for consumption – Barolo: 01 January of the fourth year after harvest; – Barolo Riserva: 01 January of the sixths year after harvest; |

| Vineyard area | 1,950.31 hectares (2020)[1] |

| Annual production | 12 980 947 x 0.75 l bottles (97 357.10 hl of wine bottled, 2020[1]) |

The aromas and flavours of Barolo

If you’re wondering “what does Barolo taste like?” the best thing to do is open a bottle and take a sip. Once you’ve tried it, you’re unlikely to forget the experience.

Barolo is a powerful wine with lots of tannins, and experts sometimes call its aroma “tar and roses”. Each mouthful brings a world of flavour. It starts with notes of liquorice, rose petals, blueberries and prunes, mingling with black pepper and cinnamon spices. This is joined by rich dark chocolate, old leather and sweet tobacco.

While utterly delicious, none of these flavours are subtle nor gentle. They instantly bring you into the moment, overpowering your senses like fire and ice to leave a lasting impression.

How the soils of Barolo impact the wine’s flavour

Although Barolo has a distinct taste, it does differ depending on where in the region the wine was produced. You’ll notice a few changes as you move from the south-east (Serralunga d’Alba) to the north-west (La Morra and Verduno). It’s fascinating that, even in the very same commune, Nebbiolo grapes may be grown on different soils – resulting in different wines.

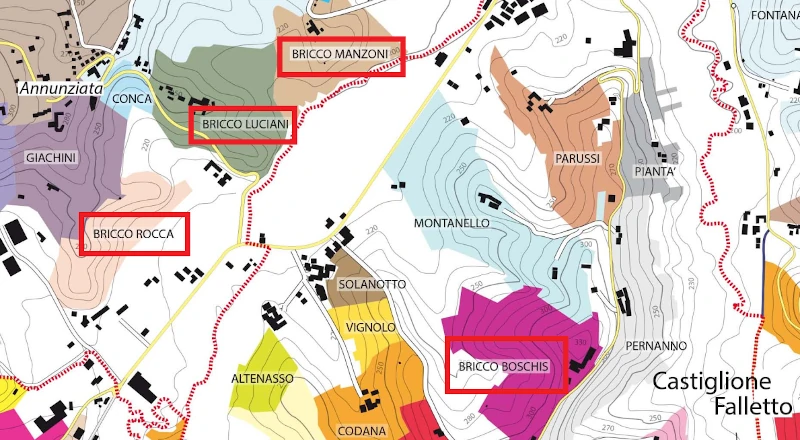

In her book “Barolo and Barbaresco”, Kerin O’Keefe wrote in great detail about how geology affects the taste of the wine in your glass[2]. Among other things, she uses the findings of Moreno Soster and Andrea Cellino of the University of Turin, who studied the soils of the Barolo region[3]. They developed a geological map of Barolo, but I always found it hard to connect the soil with Barolo’s cru vineyards. So, I’ve developed a map that overlays Barolo’s cru vineyards on the soils mapped by Soster and Cellino. This can help you to predict what the character of any Barolo you buy will be.

The soils of Langhe and Roero are made of marine sediments, as the valley of the Po river was a seabed millions of years ago. The soils consist of marls (clay and calcium carbonate) and sandstone, but their composition varies greatly across the landscape.

Calcium carbonate: austere, long-ageing Barolo

All of Serralunga d’Alba and the eastern side of the ridge in Monforte d’Alba (Perno and Castelletto crus) rests on the Lequio formation[3]. It’s the oldest part of the Barolo area, and was formed 12 million years ago in the Serravallian age[5].

This zone is home to the most powerful, austere and long-ageing Barolos.

The soil is light in colour, ranging from yellow to white. It consists of layers of clay and sandstone, rich in sand (41%) and calcium carbonate (28.9%). It is believed that calcium carbonate is responsible for the austere and powerful taste, and this area has the highest content level in the whole DOCG region – the average level is 23%.

In contrast, Roero – which is known for more elegant and approachable Nebbiolos – has a much lower level of calcium carbonate (11.3% in Vezza d’Alba)[2].

Sandy soils: structure and elegance

The central part of the ridge in Monforte d’Alba, and the southern part of Castiglione Falletto (Roche di Castiglione, Bricco Roche, Pira and Scarrone crus) sit on Diano d’Alba sandstone (Arenarie di Diano d’Alba)[3]. This soil formed in the Tortonian age, 9 million years ago[5].

This formation has a characteristic yellow colour and the region’s highest content of sand. It produces wines with both structure and elegance.

Pockets of Diano d’Alba sandstone can be found in La Morra (Bricco Manescotto, Annunziata, Santa Maria crus), and in the commune of Barolo.

Blue-grey marl: elegant, perfumed and fruitier flavours

The eastern half of La Morra, Novello, Grinzane Cavour, Diano d’Alba, Verduno and Roddi sit on Sant’Agata Fossili marls[3].

These soils are blue-grey, and consist of silt and calcareous clays. They formed 7 million years ago, in the Tortonian and Messinian ages.

These lands are known to produce the most elegant Barolos with perfumed and fruity flavours. Those wines tend to be more approachable and don’t need as much time in bottle to be ready for drinking. The ratio of calcium carbonate in La Morra is only 19.9%, much lower than in Serralunga, which produces more structured wines.

Communes and cru vineyards in Barolo DOCG

Let’s consider communes of Barolo DOCG and their cru vineyards in more detail.

The commune of Barolo

This commune gives its name to the whole denomination, and is located in the south-western part of the Barolo DOCG area.

Typical Barolo from the Barolo commune: Rich and deep with austere tannins.

Most important crus: Bricco delle Viole, Cannubi, Castellero,Liste, Sarmassa, Terlo

Notable MGA (crus) in the commune of Barolo: The major cru vineyards in the Barolo sub-zone are: Albarella, Bergeisa, Boschetti, Bricco delle Viole, Bricco San Giovanni, Brunate, Cannubi, Cannubi Boschis, Cannubi Muscatel, Cannubi San Lorenzo, Cannubi Valletta, Castellero, Cerequio, Coste di Rose, Coste di Vergne, Crosia Druca’, Fossati, La Volta, Le Coste, Liste, Monrobiolo di Bussia, Paiagallo, Preda, Ravera, Rivassi, Rue’, San Lorenzo, San Pietro, San Ponzio, Sarmassa, Terlo, Vignane, Zoccolaio, Zonchetta and Zuncai.

Castiglione Falletto

Located right in the geographical centre of the DOCG area, Castiglione Falletto has 105 hectares of Nebbiolo vines, planted on sandy soils.

Typical Barolo from Castiglione Falletto: High in fruity flavours, less tannic

Most important crus: Bricco Boschis, Bricco Rocche, Fiasco, Monprivato, Montanello, Parussi, Pernanno, Rocche di Castiglione, Villero

Notable MGA (crus) in Castiglione Falletto: Altenasso, Garblet Sue’, Garbelletto Superiore, Bricco Boschis, Bricco Rocche, Bricco Vigna Mirasole, Brunella, Codana, Fiasco, Mariondino, Monriondino or Rocche Moriondino, Monprivato, Montanello, Parussi, Pernanno, Pianta’, Pira, Pugnane, Rocche di Castiglione, Scarrone, Solanotto, Valentino, Vignolo, Villero.

La Morra

La Morra is a beautiful hilltop village in the north-west of the Barolo DOCG. This commune is often believed to produce the finest examples of Barolo, and also boasts the largest plantings of Nebbiolo in the area.

Typical Barolo wine from La Morra: The most elegant of all Barolos, it has smooth and silky tannins and beautiful floral aromas.

Most important crus: Arborina, Brunate, Cerequio, Conca, Fossati, Giachini, Marcenasco, Monfalletto, Rocche, Rocche dell’Annunziata, La Serra, Tettimorra and Santa Maria.

Notable MGA (crus) in La Morra: Annunziata, Arborina, Ascheri, Berri, Bettolotti, Boiolo, Brandini, Bricco Chiesa, Bricco Cogni, Bricco Luciani, Bricco Manescotto, Bricco Manzoni, Bricco Rocca, Bricco San Biagio, Brunate, Capalot, Case Nere, Castagni, Cerequio, Ciocchini, Conca, Fossati, Galina, Gattera, Giachini, La Serra, Rive, Rocche dell’Annunziata, Rocchettevino, Roere di Santa Maria, Roggeri, Roncaglie, San Giacomo, Santa Maria, Sant’Anna, Serra dei Turchi, Serradenari, Silio, Torriglione.

Monforte d’Alba

Monforte d’Alba is located in the south-east of the denomination area, with its surrounding production zone covering 197 hectares. Most Nebbiolo grapevines here are planted on steep slopes. Monforte is known to produce the most powerful, tannic, and long-ageing Barolos.

Typical Barolo wine from Monforte d’Alba: deep, rich, and very high in tannins. Requires the longest bottle ageing before opening. As a result, it has the best potential for ageing when compared to other Barolos.

Most important crus: Bussia, Ginestra, Castelletto, Mosconi, Le Coste di Monforte

Notable MGA (crus) in Monforte d’Alba: Bricco San Pietro, Bussia, Castelletto, Ginestra, Gramolere, Le Coste di Monforte, Mosconi, Perno, Ravera di Monforte, Rocche di Castiglione, San Giovanni

Serralunga d’Alba

Serralunga d’Alba is in the eastern part of the Barolo area, and has over 200 hectares of Nebbiolo vineyards. The soils here are rich in limestone and marl, which means the wines from this area have depth, structure, minerality, and a great potential for long ageing. Because of that Serralunga produces some of the best – and most expensive – Barolos. Having said that, some inexpensive Barolos are produced in the area too, which are very approachable in terms of price and can be drunk soon after release.

Typical Barolo wine from Serralunga d’Alba: deep and complex flavours with good structure and minerality. Ideal for long ageing.

Most important crus: Arione, Brea, Ceretta, La Delizia, Falletto, Francia, Gabutti, Lazzarito, Margheria , Ornato, Parafada, Prapò, Rionda, Sperss, Vignarionda.

Notable MGA (crus) in Serralunga d’Alba: Arione, Badarina, Baudana, Boscareto, Brea, Bricco Voghera, Briccolina, Broglio, Cappallotto, Carpegna, Cerrati, Cerretta, Collaretto, Colombaro, Costabella, Damiano, Falletto, Fontanafredda, Francia, Gabutti, Gianetto, Lazzarito, Le Turne, Lirano, Manocino, Marenca, Margheria, Meriame, Ornato, Parafada, Prabon, Prapo’, Rivette, San Bernardo, San Rocco, Serra, Teodoro, Vignarionda.

Verduno

Verduno is in the very north of the Barolo DOCG. Wines from this area offer elegant flavours of red fruits, flowers and spices. Generally speaking, they can be enjoyed at a younger age than the powerhouses from Monforte and Serralunga.

Typical Barolo wine from Verduno: Ripe, rich with elegant notes of flowers and spice.

Notable MGA (crus) in Verduno: Boscatto, Monvigliero, Massara, San Lorenzo di Verduno, Pisapola

The Nebbiolo grape

Nebbiolo is a historic varietal, and has been used to make Italian wines since the 13th century. Barolo must be made from 100% Nebbiolo, with all grapes cultivated in the area of Barolo DOCG. The wine takes it special character from – and owes its global success to – this incredible grape.

However, Nebbiolo is very demanding and difficult to grow. Not only is it very sensitive to the type of soil it’s planted on, it only ripens properly on south-facing slopes. Nebbiolo buds early (in April), and only reaches full ripeness late in the season (October). As the growing season is very long, it increases the risk of bad weather impacting the success of a vintage.

The name of Nebbiolo possibly comes from the Piedmontese word “nebbia”: the thick fog which covers the valleys in the foothills of the Alps in November, just when the harvest is over.

Fabrizio Francone, fourth-generation winemaker and producer of award-winning Barolo wine, says:

“Nebbiolo is one of the best grapes in the world because it gives incredibly sophisticated and complex wine. But it is also one of the most difficult grapes to grow in the vineyards and vinify. It need special soils and weather conditions, so only gives its best in a few small districts.”

Why Dolcetto and Barbera are planted alongside Nebbiolo

Plots which are not perfect for Nebbiolo are used for other grapes, which ripen earlier. The two typical partners for Nebbiolo are Dolcetto (usually released as Dolcetto d’Alba DOC) and Barbera (Barbera d’Alba DOC). Dolcetto ripens first, followed by Barbera.

While the flavours aren’t as powerful as Barolo, these wines made by award-winning producers are also worth trying, especially if you are interested in Piemonte.

What’s so special about tannins?

Nebbiolo is famous for creating wines that are super-charged with tannins. Tannins are natural antioxidants, and there is a body of research claiming they provide various positive health effects – if consumed in moderation, of course. Leading studies include “Contribution of Red Wine Consumption to Human Health Protection“, Snopek et al., and “Polyphenols: Benefits to the Cardiovascular System in Health and in Aging” Khurana et al.

Where Nebbiolo is grown

Nebbiolo only shows its best character in a few areas, and these are mainly in northern Italy. Unlike French grapes, such as Merlot and Chardonnay, Nebbiolo has only found success in a few other places in the world.

It is generally accepted that the best Nebbiolo wines come from the Langhe hills in Central Piemonte, from two denominations: Barolo and Barbaresco. Additionally, there are a number of areas across northern Italy historically known for excellent Nebbiolo wines.

In Central Piemonte, the hills of Roero have younger (5 million year old) sandier soil. This leads to more approachable, less tannic Nebbiolo wines when compared to Barolo and Barbaresco.

In the middle ages, the Novarra and Vercelli hills in Northern Piemonte were the source of the best Nebbiolo wines. Here, Nebbiolo is called Spanna. The Gattinara denomination was the most famous supplier to the court of The Holy Roman Emperor. Other historic denominations of Novarra and Vercelli include Ghemme, Boca, and Bramaterra.

Carema DOC in north-west Piemonte produces mountain wine – vino di montagna – from Nebbiolo planted on Monte Maletto at 300-700 m.

Piemonte’s northernmost denomination for Nebbiolo is Valli Ossolane DOC, in the Alps northwest of Lago Maggiore. Here, Nebbiolo is known as Prunent.

The Valtellina valley is located in the Lombardian Alps east of Lake Como. It produces wines from Nebbiolo (locally called Chiavennasca) planted on the terraced vineyards at 700-800 metres. Set in the cold Alpine climate, on the steepest slopes, Valtellina is known for heroic viticulture. The most interesting Nebbiolo wine produced here is Sforzat. It is made using the appassimento method, from air-dried grapes.

Valle d’Aosta DOC – especially the subzones of Donnas and Arnad-Montjoved in the Lower Valley – is also known for its Nebbiolo wines, called Picotendro. Located in Italy’s north-western corner, this province is sandwiched between Monte Bianco (Mont Blanc) and Piemonte. Donnas is often mentioned as the “mountain brother of Barolo”.

In the rest of the world, Nebbiolo grows in the Guadalupe Valley in Mexico, and in a few regions of Australia.

How Barolo wine is made

Traditional and modern styles of Barolo

The style of Barolo winemaking evolved over time, from the traditional style, to the modern style – and ultimately to the combination of the two.

The traditional style

The traditional style is the only way Barolo was made until the 1970s. Winemakers would leave the juice on the skins for up to two months. This extended maceration helped to extract a lot of colour, flavour and tannin. After this, the wine was aged for around four years in neutral, old Slavonian oak casks (botti). Such long ageing was essential to soften the hard tannins.

Barolo prepared in the traditional way was supercharged with dry tannins and high acidity. It required a lot of time in bottle to become enjoyable – sometimes as long as ten years. On the other hand, the wine had an extraordinary potential for ageing and improving in cellar for many years.

The Barolo Boys and the modern style

In the 1980s, a young generation of producers known as The Barolo Boys introduced a new, fruity style of Barolo, which was approachable upon release. The Barolo Boys used international techniques, including shorter maceration, and using small French oak barrels.

Combination of traditional and modern styles

Today, it’s quite common to find Barolo that combines both “traditional” and “modern” techniques, with a careful use of oak.

As consumer demands evolve, wineries focus on making their Barolo more readily enjoyable after release, or 4-5 years after harvest. It doesn’t need that many years to become drinkable, as was the case with the traditional style. But thanks to the age-worthiness of Nebbiolo, the wine would undoubtedly improve with 10–20 years in cellar.

The Barolo winemaking process

Alcoholic fermentation

In the cellar, the grapes are crushed and fermented with the traditional method of submerged cap fermentation.

Typically, the period of fermentation for Barolo is 20 to 30 days at a controlled temperature. This period is quite long, and helps the wine to absorb flavour and colour from the grape skins.

Some winemakers ferment their Barolo on the skins for the whole period. Others will ferment on the skins for some time, before removing the skins to finish the alcoholic fermentation without. This technique allows them to control the level of tannins in the wine.

Long maceration

After the alcoholic fermentation finishes, the wine is left in contact with the grape skins (maceration). The process takes as long as three to four weeks.

This long maceration process supercharges the resulting wine with tannins and the signature flavours that Barolo is known for. The extraction of tannins requires alcohol, which is why it’s most effective after fermentation is complete.

Stabilisation

The wine is stabilised by gravity. The particles are allowed to settle slowly, without disturbing the wine. The centrifuge or stabilisation chemicals – commonly used in mass-market wines – are not in the arsenal of the Barolo winemaker.

Oak ageing: why does Barolo have to age for so long?

To soften the powerful tannins extracted through the long maceration process, oak ageing has to be prolonged as well.

According to the Barolo wine law, the wine must rest in oak barrels for at least 18 months. Although this is the longest period for Nebbiolo wines in the whole of Italy, Barolo winemakers still tend to leave it for much longer. For example, both Francone Barolo and ForteMasso Barolo Castelletto are matured in oak for 30 months.

These days, Barolo wineries use large oak barrels, or a combination of small French barriques and large Slavonian botti. The main objective is to find a fine balance, and not overpower the precious flavours of Nebbiolo with wood.

In such large vessels, the surface area of oak in contact with the wine is relatively small. In contrast, small 225-litre Barriques of new oak may easily produce a strong flavour (vanilla, black pepper, cinnamon) and overpower the Nebbiolo’s natural flavour.

Piero Ballario is the winemaker at the Forte Masso winery. His Barolo Castelletto Riserva won Tre Bicchieri (Three Glasses) – the most prestigious national wine prize in Italy. Piero says:

“The grapes that we vinify are rich in aromas and polyphenols, therefore in the cellar we just have to extract with winemaking – and preserve and stabilize with ageing – the fruit that this outstanding vineyard is able to provide us with.”

Each winemaker will choose a method of oak ageing to create the distinctive character of their cantina. If the vintage was a successful one, and the quality of the Nebbiolo grapes is high, the winemaker will try to keep oak contact to a minimum.

Fabrizio, the winemaker and owner of Cantina Francone, says:

“You have to respect the grapes and the must to preserve the colour and the perfumes from oxidation, and to never overpower it with the oak flavour through ageing. Do not cover the wonderful bouquet of Nebbiolo with oaky notes.”

Barrel ageing allows for slow contact with oxygen, which is why the colour of Barolo becomes less ruby and more garnet – a characteristic hue for this wine. Thanks to the long ageing process, the natural harsh tannins of Nebbiolo soften and evolve. The resulting Barolo wine becomes more drinkable and enjoyable not long after release.

The best and the most challenging Barolo vintages (in plain language).

For simplicity and easy reference, we’ve put together a quick overview of Barolo vintages over the past 20 years, ranked on a scale of one to five stars. Read on for detailed vintage reports, written in plain English.

| Vintage | Overview |

|---|---|

2018 vintage: 4 stars  | A good, solid vintage. This year’s Nebbiolo grapes were healthy and able to produce classic Barolo wines – rich in flavour, with the potential for ageing. |

2017 vintage: 3 stars  | In most cases best enjoyed now, rather than cellared for decades. This was quite a hot summer, and wineries all across Italy lost a share of their harvest to the harsh, dry weather. |

2016 vintage: 5 stars  | An outstanding year that will be remembered for Barolo wines with both richness and finesse. |

2015 vintage: 5 stars  | One of the best Barolo vintages of the decade. |

2014 vintage: 3 stars  | A difficult year that pushed the winemakers’ skills to the limit. |

2013 vintage: 4 stars  | Despite challenges early in the season, this was a fine vintage. The grapes were picked three weeks later than usual. |

2012 vintage: 3 stars  | Vineyards with good water retention finished this year well, while sandy sites suffered from water stress. |

2011 vintage: 3 stars  | The year had its challenges, leading to an early harvest. |

2010 vintage: 4 stars  | Overall, a strong year ending with the perfect weather for Nebbiolo to finish ripening |

2009 vintage: 3 stars  | This vintage was a challenging one due to rainy weather, which pushed most growers to harvest early. |

2008 vintage: 4 stars  | Despite a rainy start to the season, the dry and sunny autumn led to a fabulous vintage. |

2007 vintage: 4 stars  | A fine, ripe and healthy harvest of Nebbiolo, ultimately producing excellent wines. |

2006 vintage: 5 stars  | This vintage will be remembered for its excellent quality, despite a very rough start to the year. |

2005 vintage: 4 stars  | Fine and balanced vintage with almost perfect conditions for Nebbiolo, spoiled just a bit by October rains. |

2004 vintage: 5 stars  | An outstanding vintage thanks to the perfect weather all year round. |

2003 vintage: 3 stars  | A tough, very hot year. |

2002 vintage: 2 stars  | Because of the terrible weather, this was one of the most disappointing Barolo vintages ever for most wineries. |

2001 vintage: 5 stars  | The year had a very difficult start, but in the end produced one of the best harvests. |

2000 vintage: 4 stars  | This was a rather good year for Barolo. Nebbiolo is a late-ripening grape and the season turned out to be long and favourable. |

Barolo vintage reports

2018 vintage: 4 stars

A good, solid vintage. This year’s Nebbiolo grapes were healthy and able to produce classic Barolo wines – rich in flavour, with the potential for ageing.

The year started with a long, rainy winter, with the Earth replenishing the water it lost during the dry, hot summer of 2017. On the plus side, there were no spring frosts. The vines went through all of the natural steps right on schedule, with no surprises. In the end, they delivered a crop of healthy Nebbiolo grapes in the usual time for harvest in mid-October.

Barolo winemaker Paolo Demarie says about the 2018 vintage:

“2018 Barolo & Barbaresco have strong spices and balsamic notes with strong tannins. These are wines that need a few more years to be ready with an excellent predisposition to aging.”

2017 vintage: 3 stars

In most cases best enjoyed now, rather than cellared for decades. This was quite a hot summer, and wineries all across Italy lost a share of their harvest to the harsh, dry weather.

Before the arid summer began, the year started with April frosts. From May, the spell of hot and dry weather lasted all the way through to August. La Morra, the village of Barolo, and the western parts of the Barolo area – where the soil retains more water – coped with it considerably better, but it was a challenging season overall.

Because of the hot weather, the grapes matured earlier. The Nebbiolo harvest started in early September, rather than October. Even so, the grapes turned out to be riper and more jammy.

Nevertheless, good wineries managed to craft fine, well-balanced Barolo by only using healthy grapes and producing much smaller volumes. In October 2021, we tasted a few 2017 Barolos and they were really delicious and “ready”. One thing to note is though the wine tastes nice, the quick, early ripening means it has less acidity than is ideal for long ageing.

2016 vintage: 5 stars

An outstanding year that will be remembered for Barolo wines with both richness and finesse.

The winter got enough rain to create reserves of water. The spring was cold and very rainy, delaying the development of the grapes by a couple of weeks. The summer of 2016 was excellent, and the warm and sunny weather lasted throughout the season until harvest.

The big difference from 2015 was that there were no days of scorching heat: the weather was consistently perfect for grape ripening. As a result the grapes had the perfect level of sugar. The Barolo wines of 2016 are superb, with lots of richness and structure, but more finesse and elegance than 2015.

2015 vintage: 5 stars

One of the best Barolo vintages of the decade.

The year started with a snowy winter, which helped to saturate the soil with water for the upcoming season. The spring was warm, with earlier-than-normal flowering and formation of berries. A rainy May was followed by a dry and hot summer, with daytime temperatures in July often soaring to above 40°C. But the heat caused no water stress because there was plenty of water in the soil, so the vines thrived and developed lots of healthy grapes.

In fact, the vines formed too many grapes for such an excellent vintage, so vine-growers tirelessly cut everything except the best bunches – so-called “green harvest”. The summer sun helped the grapes to develop the perfect levels of sugars and acids, as well as the phenols responsible for deeper colours, complex flavours and tannins.

Thanks to the health and the balanced development of the grapes, the 2015 vintage of Barolo is considered one of the best ever.

2014 vintage: 3 stars

A difficult year that pushed the winemakers’ skills to the limit.

In 2014 the spring came early, so the growing season started earlier than usual. The weather in early summer was as expected. In July, a combination of lots of rain and warm weather created the perfect conditions for mould to spread in the vineyards. Furthermore, many sites across the Barolo area were hit by hailstorms, wiping out a large number of grapes.

Overall, due to the earlier-than-normal start of the season and the problems with rain, grapes could not develop sufficient levels of sugars and phenols in many sites. As a result, wines from 2014 tend to have a paler colour, lower levels of alcohol, and sometimes sour notes.

2013 vintage: 4 stars

Despite challenges early in the season, this was a fine vintage. The grapes were picked three weeks later than usual.

The spring was very cold and wet, with tons of rain, so the growing cycle was delayed by a few weeks. Although the weather in June and July was perfect, with lots of sun, it was not enough to compensate for the delays which happened in the spring.

Fortunately, the weather in September and October was sunny and warmer than usual, which extended the ripening season and helped the Nebbiolo reach its full maturity.

The grapes were harvested during the last days of October into early November. The resulting Barolo had excellent depth of colour, complex flavours and ripe tannins.

2012 vintage: 3 stars

Vineyards with good water retention finished this year well, while sandy sites suffered from water stress.

The winter was harsher than usual, with bitter cold snaps and a lot of snow. But on the other hand, it helped to create water reserves in the soil. The spring was cool and wet. Temperatures rose substantially in May, so budding happened a couple of weeks early.

Starting from June, the weather turned exceptionally hot and dry with scorching temperatures of 38°C recorded in August. But thanks to the water reserves from the wet spring, there were no major issues.

Harvesting started in early October, which was earlier than usual. Again, like in the previous year, the harvest was too early. The grapes hadn’t developed enough sugars, depth of colour or tannins to qualify for a perfect vintage.

2011 vintage: 3 stars

The year had its challenges, leading to an early harvest.

The winter was normal, with enough snow and rain. But an unusually warm April brought the grape growing cycle back by two weeks. The cool summer concluded with a very hot and dry August, with 10-15% of grapes lost to sunburn and water stress.

A bit of rain in September brought relief, and the vines bounced back. Unfortunately, due to the early start of the season, the harvest took place earlier than normal.

The resulting vintage was okay, although the Nebbiolo could have benefited from a later harvest to complete its development of colour and tannins.

2010 vintage: 4 stars

Overall, a strong year ending with the perfect weather for Nebbiolo to finish ripening.

The winter was long and hard. Lots of snow meant that there was enough water in the soil for a good start to the season. The spring and summer months were rather cool though, with more rain in July and August. Because of that, grape ripening took longer than normal.

However, the end of August and September were excellent, with lots of daytime sun and cool nights. This created perfect conditions for Nebbiolo to ripen completely and partially recover after the rainy summer.

The resulting harvest was healthy, with some wineries producing excellent wines.

2009 vintage: 3 stars

This vintage was a challenging one due to rainy weather, which pushed most growers to harvest early.

There was plenty of snow in winter, and the spring was rainy too. This helped the soil to accumulate lots of water for the coming season, but unfortunately led to the spread of parasites and fungi attacking the vines. Happily, it wasn’t as bad as 2008.

The summer was cool, with lots of rain. In the end, because of the rain, the harvesting time was brought forward. This vintage will be remembered as a very tough one. With the exception of a few vineyards, the grapes did not complete their phenolic development and so the resulting wine had a pale colour and thin flavour.

2008 vintage: 4 stars

Despite a rainy start to the season, the dry and sunny autumn led to a fabulous vintage.

This was a very hard year. Heavy rains started in May, followed by the cold and wet summer. This led to fungi and parasites attacking vineyards between May and July. Growers worked really hard, and unfortunately had to remove lots of plants. This was followed by strong winds and hail storms, reducing the yields by about 10-15%.

Luckily, warm and dry sunny weather set in at the end of August and lasted until October. This helped the Nebbiolo to develop the desirable levels of acids, sugars and tannins.

Though this year saw a really rough summer, the quality of the resulting Barolo was solid: ranging from good to excellent depending on the winery.

2007 vintage: 4 stars

A fine, ripe and healthy harvest of Nebbiolo, ultimately producing excellent wines.

The mild winter and warm spring of 2007 meant that the vines flowered 20 days early. In June, this wonderful start was interrupted by a cool and rainy spell. It was followed by hail storms hitting large areas in Castiglione Falletto, Barolo and Monforte d’Alba, where up to 15% of the grapes were lost.

The weather during the growing season was rather unstable, with the rains and hails of June followed by a hot and dry July and cold August. Despite all of the challenges, the vines produced wonderfully healthy grapes. As the season started earlier than normal, the harvest also took place 20 days earlier, which did not affect the excellent quality of the resulting wines.

Although not as perfect as the previous vintage, 2007 is still considered an excellent year.

2006 vintage: 5 stars

This vintage will be remembered for its excellent quality, despite a very rough start to the year.

The season started with an extremely cold winter, with above average levels of snow and rain. The winter stayed in Langhe for long than usual, and the weather did not turn until April. But the spring was very warm, followed by a hot dry summer with temperatures reaching 35°C, with no rain.

In September, hard rains hit the area and ended the dry spell. But the good thing is, the excess water was absorbed by the dry soil and didn’t cause the grapes to swell; which could otherwise dilute flavours.

The harvest of 2006 was excellent. The Nebbiolo grapes had complex flavours and healthy levels of acids and sugars, ultimately producing Barolo of excellent quality.

2005 vintage: 4 stars

Fine and balanced vintage with almost perfect conditions for Nebbiolo, spoiled just a bit by October rains.

This was a normal year, with a sunny summer that was slightly cooler than usual. The rainfall was patchy, with some areas receiving a lot of it and others not getting a single drop for months on end.

The season started with a mild winter, which delayed budding because the cold lasted longer than normal. But late spring and early summer were exceptionally warm. July and August were sunny and cool, with very little rain. As a result, the Nebbiolo grapes developed in excellent health, producing wines of good quality.

Rains came to Barolo at the beginning of October, so the grapes had to be harvested in bad weather.

2004 vintage: 5 stars

An outstanding vintage thanks to the perfect weather all year round.

Winter rain and snow helped the soil to recover from the hot and dry season of 2003. The spring was quite wet too, but it was followed by a very fine summer, with a perfect balance of sunny and rainy days. This helped the grapes to develop and ripen well. In August, a few vineyards in Barolo took some damage from hailstorms.

The growing season ended with a beautiful period of warm and dry sunny weather in September and October. The grapes completed their development and had the perfect amount of sugars, polyphenols and acids. The harvest days in October were either sunny or cloudy, and grapes were picked without interruption from bad weather. This helped to produce a high-quality vintage.

2003 vintage: 3 stars

A tough, very hot year.

This was a very hot year, with the air temperature 10°C hotter on average than the norm for Langhe, and almost no rainfall. By the beginning of September, the area saw only 265mm of rain, down from 830mm in 2002 for the same period. A large number of grapes were damaged by sunburn. Because of the water stress, the yield was greatly reduced. But it’s also true that the water stress helps to concentrate flavours and produce better wines.

A small number of vine-growers in premium locations managed to produce good wines, but overall it was a very hard year for Barolo.

2002 vintage: 2 stars

Because of the terrible weather, this was one of the most disappointing Barolo vintages ever for most wineries.

The cold spring was followed by a cold, rainy summer. Everywhere in Langhe, grapes were attacked by grey mould. Vine-growers toiled really hard to save the grapes, and in early September, the expectations weren’t too bad. But it all ended later that month, when hailstorms hit the denomination of Barolo really hard – taking out up to 40-45% of the grapes.

So, in the end, most respectable producers skipped the 2002 vintage. In general, this wasn’t a Barolo worth keeping. Let’s forget this year and move on.

2001 vintage: 5 stars

The year had a very difficult start, but in the end produced one of the best harvests.

The winter was warmer than usual, with lots of rain, which led to early budding. In April, Langhe was hit with a devastating cold spell freezing the air to -5°C, which was followed by a hail-storm. After the weather returned to normal in summer, new challenges arose in August, which was very hot and dry. September was rainy and cold, with water swelling the grapes. But this was followed by a sequence of cool and sunny Autumn days, which helped the Nebbiolo to complete its cycle in perfect health and develop rich tannins and flavours.

In the end, the grapes needed more time to ripen, so the harvest was pushed back by a few days. The wait paid off: 2001 is considered one of the best vintages for Barolo. The wine of 2001 has deep colours, rich flavours and powerful tannins.

2000 vintage: 4 stars

This was a rather good year for Barolo. Nebbiolo is a late-ripening grape and the season turned out to be long and favourable.

The winter was mild, with intermittent snowfall. The spring was wet, which increased the risk of attacks by fungi, but it was followed by a dry and sunny summer, which helped the grapes to mature in excellent health. August and early September were very hot. The weather turned at the end of the ripening season in late September and early October: there was a good mixture of sunny and cloudy days, with a bit of rain and a gradual drop in air temperature.

The resulting Barolo wine had deep colours, complex flavours and structure, and well-developed tannins.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the best Barolo wine?

If you want to cut to the chase and find the best Barolo to buy, start by considering the following points:

Where it was made

The best Barolo wines come from single vineyards (the technical term is “vigna”), which are clearly marked on the label. Historically, some of those vineyards produce outstanding Barolos in most vintages. Those vignas are world-famous, and command exorbitant prices. Other, lesser-known vignas, are priced quite reasonably.

The next level of quality and prestige is MGA, or menzione geografica aggiuntiva – additional geographical naming. In the common tongue, instead of MGA we use the word “cru”. All MGAs are likely to produce rather good – or even outstanding – wines. But of course it all boils down to the particular site within MGA, and to the vintage. In hilly areas like Barolo, rain and storms affect different vineyards in bizarrely different ways: a hailstorm may hit one locality while passing the other. So each vintage may produce totally different wines, from grapes grown just a few hundred yards apart.

Finally, some producers mention the name of the commune (village) on the label rather than a vigna or MGA. These are the top five Barolo communes to look out for:

- The commune of Barolo

- La Morra

- Castiglione Falletto

- Monforte d’Alba

- Serralunga d’Alba

Finally, if the label doesn’t mention a vigna, MGA or commune, check what year is printed on the label (vintage), and if the wine has won any awards. Some lesser-known winemakers can surprise everyone else and produce fabulous wines that win top awards. Such winemakers don’t (yet?) have a famous name, and tend to offer the best value for money. So it’s always worth checking who’s won top scores in this year’s Decanter or Gambero Rosso awards.

When it was made

Barolo harvests in 2010, 2015, and 2016 were remarkably good, and the resulting wine is likely to be brilliant. Tom Hyland wrote in Forbes that the 2016 vintage would be “one of the all time great vintages for Barolo“, so if you have a bottle of that you’re very lucky. On the other hand, 2002 and 2003 were not as good. 2017 was also quite challenging, as it was a very hot year and growers had to start picking at the end of September – a month ahead of the usual time.

Do your research and buy a good vintage. Not only will it be a really enjoyable drinking experience, it’s also likely to appreciate in value should you decide to hold onto it.

Awards

With so many options available, how can you pick the best Barolo if you aren’t an expert? An international award is perhaps the most obvious indication of wine quality. Why? It’s an impartial assessment. Experts compare lots of wines and aren’t eager to sell you anything.

At the end of this article, I share a few recommendations of award-winning Barolo wines from wineries I personally visited. They are made by winemakers I have spoken to, and I am happy to make these recommendations. Of course, there are plenty of other excellent Barolo wines on the market.

How much should a good Barolo wine cost?

A review of a hundred Barolos

Recently I analysed over a hundred Barolos on sale in the UK, and wrote the article What is the right price for Barolo? With bottles costing anywhere from £16 to £260 and upwards, it’s a really broad range. For me the main question is, at what price will you get a high-quality wine that will give you the experience that you expect from such a legendary name?

Whichever way you look at it, you’re going to struggle to find a bottle for a tenner. The price of Barolo is very much based on the following: the quality of the wine, and whether the vineyard consistently produces good wine, year after year. Such vineyards will be able to command higher prices. And finally, the merchant’s marketing ambition.

The three tiers of Barolo

From cheapest to most expensive, there are three tiers of Barolo wine:

- High-volume “supermarket Barolo” produced by farmer cooperatives and commercianti (merchants who buy grapes from growers) – £16-30

- Solid quality, small-volume Barolo produced by family vineyards – £30-75

- High-end “connoisseur Barolo” – £75-220

Having spoken to Barolo winemakers in Italy, I personally believe that the solid quality Barolo from family vineyards offers the best value for money. You can definitely find excellent wines between the £30 and £75 price point. If you want to learn more about the prices of Barolo read what is the right price for Barolo?

What food goes with Barolo wine?

Barolo is the perfect wine to enjoy with a good meal, and many Italians choose it for special occasions. If you’re looking for some dinnertime inspiration, our favourite food bloggers shared their favourite Barolo-friendly recipes with us:

- Braciole di maiale alla brace (Grilled Pork Chops)

- Bistecche alla Pizzaiola (Beef Filets with Tomato Sauce)

- Beef Roast Simmered In Red Wine (Brasato Al Barolo)

- It’s grilling time! – Braciola alla griglia (Grilled beef roll)

- The original “Ossobuco alla Milanese”

- Meatballs with lemon and fennel

- Roast Boneless Leg of Lamb stuffed with Herbs and Garlic

Want more? Check out our article on Delicious dishes to pair with Barolo, Barbaresco and Barbera.

How long should you keep Barolo wine for?

If you like well-developed wines, hold your Barolo for at least 7 years before opening. Nebbiolo has a remarkably high level of tannins, and if the wine is opened too early their harshness may overwhelm you. Since I do a lot of wine tastings, I don’t mind tannic wines (or should I be honest I’m a bit addicted to tannic wines?) – so a 4 year-old Barolo wouldn’t scare me as much as someone else.

After 7 years of softening in the bottle, the wine will give you a far more enjoyable experience. The hard tannins will have become velvety, melting into aromas of smoke, cinnamon, leather, chocolate and sweet tobacco.

Good things come to those who wait, and Barolo will reward you if you decide to hold it for longer. Its flavours will continue to develop for 15 or 20 years, and the wine will age beautifully. After that, the fresh fruitiness will start to fade and be replaced with the aroma and taste of dried black fruits.

Where can I buy high-quality Barolo?

Now that you know a little bit more about the legendary Barolo wine, why not pick up a bottle or two? We’ve got some truly fantastic Barolo and Barbaresco wines in stock:

References

[1] Istituto di Servizi per il Mercato Agricolo Alimentare (ISMEA) http://www.ismea.it/

[2] Kerin O’Keefe, Barolo and Barbaresco, University of California Press, 2014

[3] M. Soster, A.Cellino, La Zonazione del Barolo, Quad. Vitic. Enol. Univ. Torino 2005-2006

[4] Disciplinare Di Produzione Dei Vini A Denominazione Di Origine Controllata E Garantita “Barolo” modified on 17.04.2015, Consorzio di Tutela Barolo Barbaresco Alba Langhe e Dogliani, http://www.langhevini.it/

[5] E. Bonelli, Geological Origins Of The Barolo Winegrowing Area https://arnaldorivera.com/en/geological-origins/