Guide to Amarone della Valpolicella DOCG and Valpolicella DOC wines

Amarone della Valpolicella DOCG and Valpolicella DOC are some of Italy’s most legendary wines, which both come from the same winemaking area. This lies north of the city of Verona – in the foothills of the Lessini Mountains, on the southern edge of the Venetian Alps. While Amarone della Valpolicella DOCG and Valpolicella DOC share the same territory, they are produced in very different ways.

Amarone is a dry red wine made from air-dried (passito) grapes. The dried grapes contribute rich and concentrated red fruit flavours. Amarone is aged – typically in oak barrels – for at least two years, and Amarone Riserva for four years.

Valpolicella DOC is a dry red wine. Standard Valpolicella wine doesn’t have to be aged, and is typically made in a fresh unoaked style in stainless steel vats. Valpolicella Superiore must be aged for at least one year, offering richer flavours.

Valpolicella Ripasso is even more complex. It is made by re-fermenting the wine with unpressed Amarone grape skins, and adding up to 15% of Amarone wine. Ripasso is aged for one year or more.

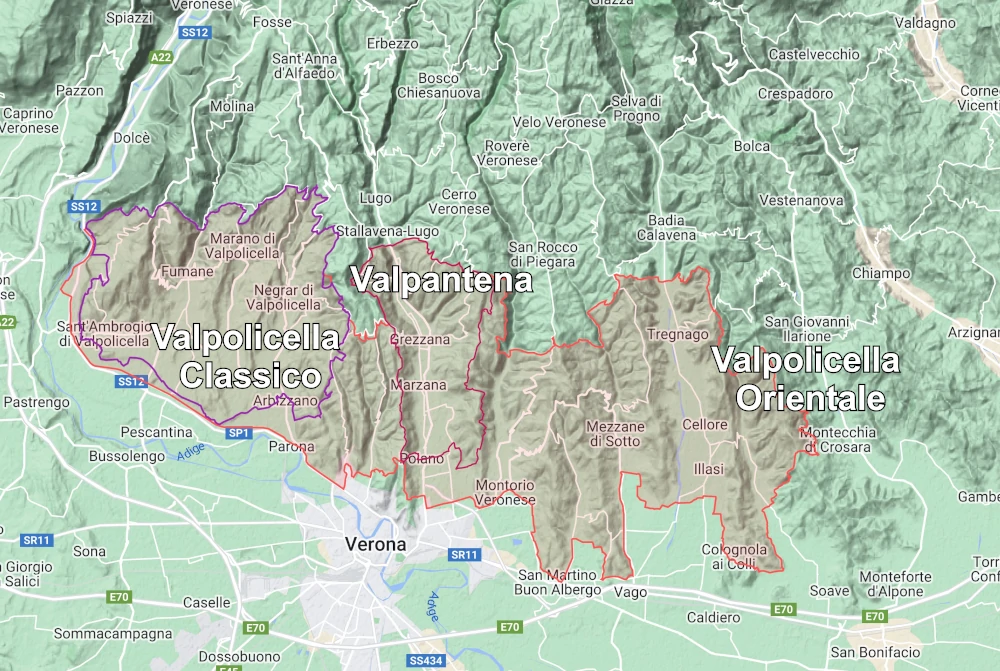

Valpolicella has two official sub-zones that can appear on the label: Classico and Valpantena. Valpolicella Orientale (eastern Valpolicella) is not an official designation, but this area is home to many innovative wineries recognised for their fruity and elegant wines.

Quick links

Table of contents

- How to choose Valpolicella wine: chart of Valpolicella wine styles

- Valpolicella wine types and denominations

- Valpolicella and Valpolicella Superiore DOC

- Valpolicella Ripasso DOC

- Amarone della Valpolicella DOCG

- The terroirs of Valpolicella and how they influence taste

- Valpolicella and Amarone grapes and “The Valpolicella Formula”

- Permitted Valpolicella grapes

- Vine training: Pergola Veronese and Guyot

- References

Valpolicella at a glance

The winemaking area of Valpolicella is home to several dry wine denominations, all sharing the same territory: Valpolicella DOC, Valpolicella Ripasso DOC and Amarone della Valpolicella DOCG. The region also produces sweet wine: Recioto della Valpolicella DOCG.

Valpolicella lies 6 km east of Lake Garda, and sits just north of the city of Verona. The eastern border is the province of Vicenza and Soave DOC – a famous white wine denomination. The Lessini mountains, which form part of the Venetian Prealps, form the northern boundary. They protect Valpolicella from the cold Alpine winds.

Valpolicella has two official sub-zones that can appear on the label: Classico and Valpantena. Valpolicella Classico is the historic heartland, nearest to Lake Garda. Following a surge in demand for Valpolicella wines, in 1968 Valpolicella was expanded to include the valley of the Valpantena river and Valpolicella Orientale – the hills lying to the east of Valpantena. In fact, Valpolicella Orientale’s easternmost valleys of Ilasi and Tramigna are shared with the Soave denomination.

Valpolicella offers a range of wine styles, all made from a combination of Corvina, Corvinone and Rondinella grapes – a blend known as the Valpolicella formula. Wineries are allowed to add up to 25% of other permitted grapes to develop their unique house blend.

Some winemakers will add Molinara and Oseleta – we’ll look at each of those varietals below (jump to: Valpolicella and Amarone grapes). Each winery uses its own unique formula that matches the specific terroir – for example 45% Corvina, 45% Corvinone, 5% Rondinella and 5% Molinara. As each blend is based on the strengths of the local terroir, one combination is not necessarily better than any other.

How to choose Valpolicella wine: chart of Valpolicella wine styles

There are several styles of wine bearing the name Valpolicella. The unoaked and fresh Valpolicella bursts with flavours of fresh wild strawberry, raspberry and cinnamon. Valpolicella Superiore has the added complexity which comes from oak ageing. Finally, Valpolicella Ripasso is co-fermented with Amarone skins, and it’s known for super complex notes of red fruit preserve, leather and sweet tobacco, as well as nutmeg and spices.

Amarone wine is unique because it’s a dry wine made from grapes dried indoors in special lofts. It offers dense, intensely concentrated flavours of candied strawberry, prunes, raisins, cinnamon spice and dark chocolate.

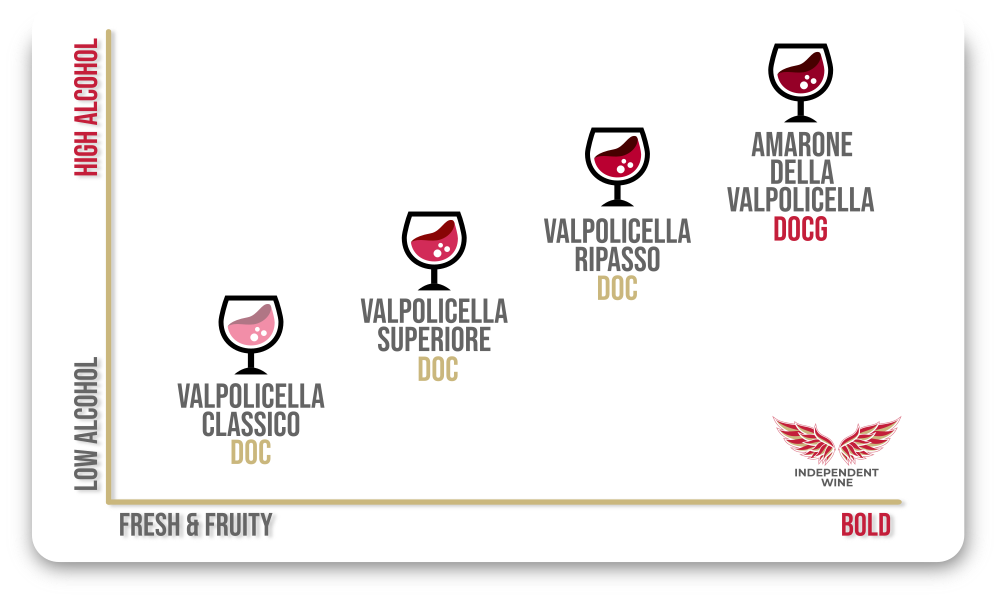

This chart of Valpolicella wine styles should be helpful in understanding how these wines differ. The X axis indicates flavour profile, from “fruity and fresh” to “bold and concentrated”, while the Y axis positions them by their alcoholic strength.

This shows their different characters, rather than implying that some are “better” or “worse” than others. The one you like best will depend on your personal taste and the occasion.

How Valpolicella dry wines compare: from fruity to bold, and from low to high ABV

Valpolicella wine is made to be drunk young and fresh, showing the pure essence of the grape. It’s not inferior to the bold Amarone made from dried grapes.

Valpolicella is like an agile cheetah, while Amarone is like a powerful lion – they’re just different animals.

Valpolicella wine types and denominations

Let’s have a closer look at the different types of wine you can find in Valpolicella.

We’ll start by going back in time to the 7th– 5th century BCE, when these lands were populated by the Rhaeti. This is how far back we can trace winemaking in Valpolicella. This area later became the Roman province of Raetia, and the wine became known as “retico” [7].

The name Valpolicella itself shows that winemaking was an important business here during that time, as it comes from the Latin phrase Vallis Poli Cellae – the valley of many cellars.

In 1881, Stefano De Stefani – an archaeologist from Verona – outlined the first delimitation of the Valpolicella winemaking zone, and documented all the traditional production methods that were in use there. Valpolicella was officially registered as a denomination in 1968, when the Italian government adopted its first set of winemaking rules and created the Valpolicella Denominazione di Origine Controlata (DOC).

But, since Valpolicella produces wines in so many different styles, it proved impossible to keep them all in the same rulebook. While Valpolicella is a youthful dry red wine produced without ageing, Amarone is made by fermenting dried grapes and ageing them for two years. Ripasso calls for re-fermentation with added Amarone grape skins and then aging for another year.

Because of that, in 2010 several new denominations were created to honour each specific style. These are the types of wines you will find in Valpolicella today:

- Valpolicella DOC (formed in 1968)

- Valpolicella Ripasso DOC (formed in 2010)

- Amarone della Valpolicella DOCG (formed in 2010)

- Recioto della Valpolicella DOCG (formed in 2010)

DOC and DOCG: levels of quality of Valpolicella wines

So, why are some Valpolicella wines labelled DOC and some DOCG? Both designations mean that the wine is produced according to a rulebook called disciplinare di produzione, and meets its quality criteria. However, the production rules for DOCG are stricter than for DOC.

To show that the wine has been tested and meets the DOC and DOCG standards, each bottle has a numbered label called fascette. To issue a fascette, the Conzorzio tests samples of wine from each vintage in a chemical laboratory. It also conducts expert tasting to ensure the wine’s flavour follows the typical style.

Winemakers should test one sample in the whole vintage to obtain a DOC fascette. But for DOCG, each batch is tested separately before bottling. That’s why DOCG provides the highest level of quality available in Italy. But, as each fascette costs money, it also adds about €0.25 to the average cost of each bottle.

Read more about the quality levels of Italian wines in our Ultimate Guide to Italian Wines.

Now, let’s look closer at each of the wines from Valpolicella.

Valpolicella and Valpolicella Superiore DOC

What type of wine is Valpolicella?

Valpolicella DOC is a dry red wine. Standard Valpolicella wine doesn’t have to be aged, and is typically made in a fresh unoaked style to showcase the pure character of the grapes and the terroir. A well-made Valpolicella wine bursts with aromas of fresh strawberries, raspberries and red cherries, underpinned by notes of nutmeg, cinnamon and white pepper.

Try Valpolicella wine:

If you see the word “Superiore” next to Valpolicella (Valpolicella Superiore), this means that the wine has been aged for at least one year. Depending on the desired style, the winemaker can either use oak barrels, stainless steel vats or concrete tanks. As a result of the ageing process, the wine develops more complex notes of dried cranberries, dark chocolate and leather.

Some premium examples of Valpolicella Superiore are aged for a longer time. For example, Rubinelli Vajol age their wine for 24 months in large French oak barrels. There, the wine picks up desirable flavours of cinnamon, chocolate and prunes. After that, the wine is matured for eight more months in bottle, bringing the overall process to just over three years. This is longer than for “standard” Amarone wine.

Try Valpolicella Superiore wine:

How is Valpolicella wine made?

The rules of Valpolicella require that the grapes are grown in a traditional way to preserve their authenticity. As a result, only traditional training systems are permitted: Spalliera (Guyot) or Pergola Veronese (see “Vine training: Pergola Veronese and Guyot” below).

Harvest time usually takes place during the third and fourth weeks of September. The growers cannot exceed the maximum yield of 12 tonnes of grapes per hectare. The harvested grapes should be quite ripe and have enough sugar to produce wine with the minimum alcohol level of 11%. [2]

Fermentation takes place at a controlled temperature. For Valpolicella, this takes around two weeks – enough for a lively character and lighter colour. For Valpolicella Superiore it can take as long as three weeks to extract more colour and flavour. Winemakers usually choose stainless steel for this wine rather than oak barrels, in order to preserve the fresh aromas of red fruit.

Valpolicella Ripasso DOC

What type of wine is Valpolicella Ripasso?

Ripasso means re-pass, or second fermentation. This refers to the extra complexity which is brought by Amarone grape skins, which are added to the liquid during the fermentation process. This wine tastes of fresh cherries and strawberries, boosted by bold undertones of cherry preserve and dried cranberries.

How is Valpolicella Ripasso wine made?

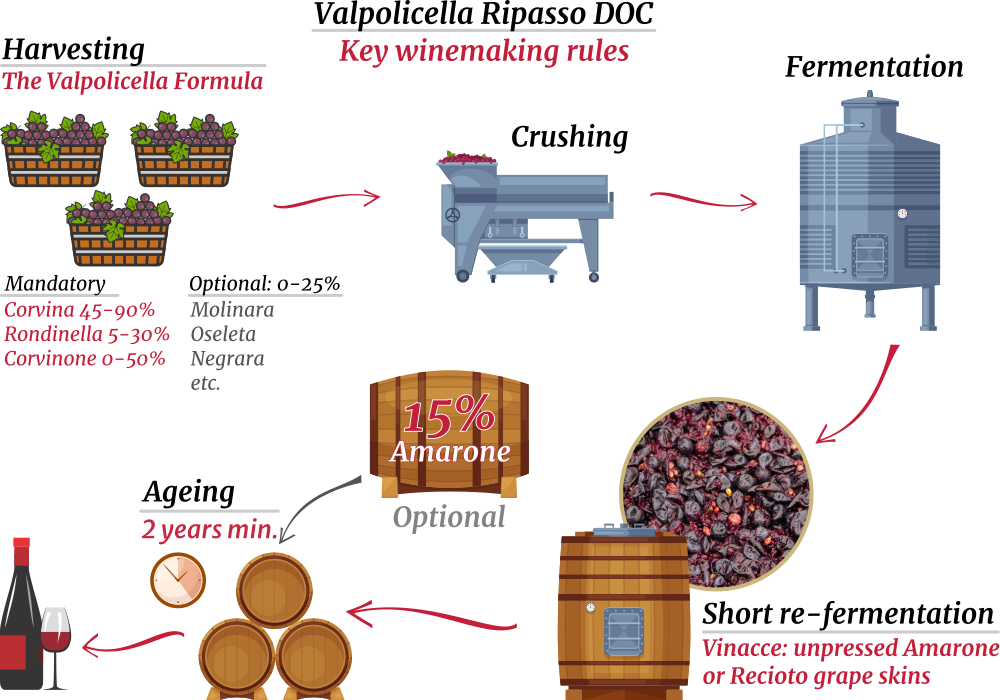

The method of winemaking for Ripasso has been in use in Valpolicella for a long time. It was perfected in the 1960s by the Masi winery (among others) and was officially registered as a new denomination Valpolicella Ripasso DOC in 2010. The key winemaking rules are shown on the diagram below.

First, grapes are fermented as normal – typically in stainless steel tanks at a controlled temperature – to produce dry Valpolicella wine.

Vinacce: Amarone grape skins

In parallel, freshly prepared Amarone wine is drained from its tank. The leftover, unpressed wet grape skins and lees – called vinacce – are still undergoing a residual fermentation process.

Then, the Valpolicella wine is poured to the tank with vinacce. This effectively starts a second fermentation which lasts for 10–15 days. As well as increasing the level of alcohol, this adds structure and an intense fruity flavour to the wine.

Finishing touches

Up to 15% of finished Amarone wine may be added to the Valpolicella Ripasso, if the winemaker thinks it will benefit the taste [3].

Another technique used in Ripasso winemaking is adding a small quantity of half-dried grapes to the Valpolicella wine. Although not defined in the wine law, this technique is considered traditional. It helps to make the wine taste richer and bolder.

Ageing

Valpolicella Ripasso wine has to be aged in oak and then in bottle for at least two years before it’s ready for release. As it ages in oak barrels, small amounts of oxygen pass through the wood and into the wine. This oxidative ageing breaks down the tannins, giving them a softer and more velvety texture.

At the same time, the flavours of fresh red berries – such as strawberry and raspberry – mature into tastes of dried or candied fruits. Oak also contributes its own tannins and flavous like vanilla, black pepper spice, espresso and dark chocolate. So overall, oak ageing adds a degree of complexity which many wine lovers find appealing.

Try a Valpolicella Ripasso wine:

Amarone della Valpolicella DOCG

What type of wine is Amarone?

Amarone is dry red wine with concentrated flavours, made from half-raisined (passito) grapes. The best Amarone wines are famous for their intensely concentrated flavours of candied strawberry, dried cherries, cinnamon spice, chocolate and cocoa.

Because it’s made from dried grapes, Amarone has a rather high alcohol level; typically 14.5-15.5% ABV.

Pamela Bicchi, AIS Master sommelier and wine journalist, says:

“According to legend, Amarone was discovered by accident in the 1930s. Adelino Lucchese, the cellar man at Villa Novare, forgot one barrel of sweet Recioto wine in the cellar. When he discovered it a few months later, he worried that the wine would have gone bad and that he would be fired. He called the winemaker and they tasted it together. Much to their surprise, the wine hadn’t gone bad. In fact, it was even better!”

Pamela explains:

“The slow barrel fermentation had given it more structure and body. Additionally, the remaining sugar in the Recioto was transformed into alcohol, so the wine gained more power as well. As it was no longer sweet, they decided to name it “bitter”. But, to show that it’s different from traditional bitter herbal liqueurs called “amaro” (such as “Amaro of Villa De Varda”) they coined a new name – “big bitter” (Amarone in Italian).”

How is Amarone wine made: the appassimento method

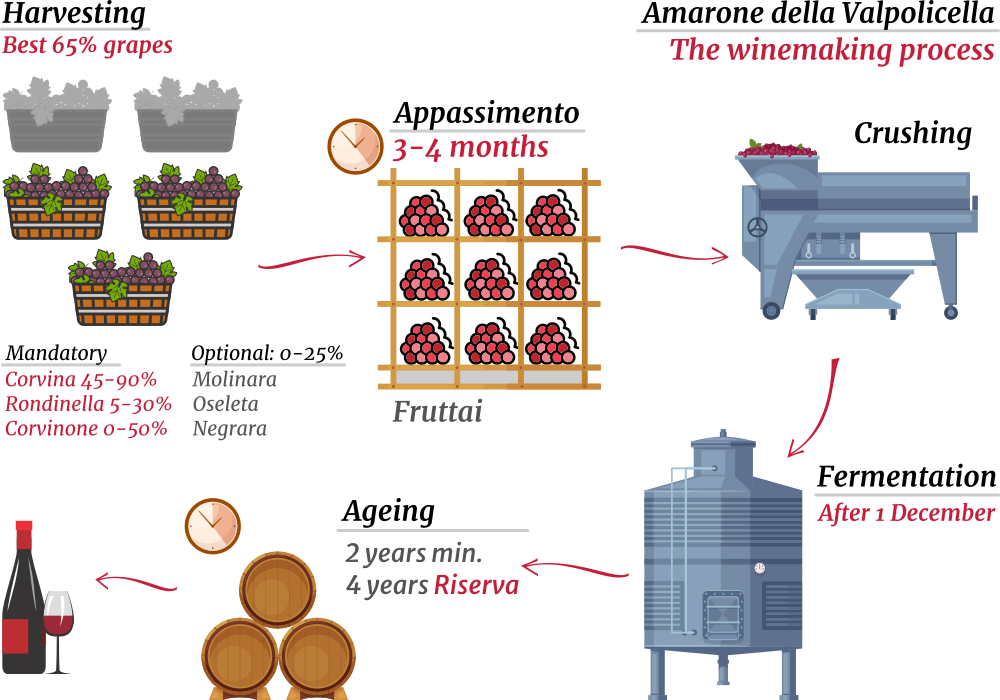

Amarone wine is made using the appassimento method. Its purpose is to concentrate levels of sugar, acid and flavour in the grapes.

Whole grape bunches are harvested by hand, to avoid any skin damage which may occur during machine harvesting. During the drying process, damaged skins can be a breeding ground for parasites. This could destroy the entire harvest.

Wine law says that only 65% of the harvested grapes can be used for Amarone. This pushes wineries to select only the healthiest, fully ripe grapes.

The key Amarone della Valpolicella winemaking rules are shown in the diagram below:

Drying racks: arele or graticci

The bunches are laid on wooden racks covered by bamboo sticks, called arele or graticci. These days, many producers choose to use plastic crates instead.

What’s better – plastic crates or bamboo – is a controversial topic in Valpolicella. Some winemakers prefer bamboo as it’s traditional, while others prefer plastic because it’s easier to keep clean.

Grapes are laid in a single layer, to avoid crushing or bruising the fruit.

Fruttaio

The long-term drying of grapes for Amarone takes place in indoor lofts, called fruttaio.

Fruttatio may be equipped with large industrial fans to circulate the air. This also reduces the risk of disease, and helps to naturally reduce or completely eliminate the use of protective chemicals – especially important for organic winemaking.

Grapes will remain in fruttaio for three to four months. During this time, the berries practically become raisins and lose about 30% of their weight. The resulting grapes have highly concentrated levels of sugar, acid and – most importantly – flavour.

Noble Rot – Muffa Nobile

Noble Rot – botrytis or Muffa Nobile – appears on the drying grapes while they rest in fruttaio. Each winemaker will decide what level of Noble Rot is desired, depending on their house style.

Noble Rot increases the level of glycerol in the grapes and improves flavour complexity in the wine. It also adds attractive notes of dried apricots, raisins and nuts.

Fermentation

The dried grapes are then crushed and fermented. Because of the high sugar levels in the dried grapes, fermentation is slow. Winemakers must manage the process very carefully to ensure the sugar is fermented.

The ultimate Amarone wine is deep, bold and dry, with about 14–15.5% alcohol. The wine law (disciplinare di produzione) does not permit alcoholic strength lower than 14%.[1]

Amarone ageing rules

The Amarone della Valpolicella rulebook (disciplinare di produzione) has some of the longest oak ageing requirements in Italy. Even “regular” Amarone wine must be aged for at least two years. For Amarone Riserva, the minimum period is four years.

Ageing can take place in a combination of oak barrels, stainless steel tanks or in bottle.

What is the price of Amarone wine (or Why is Amarone so expensive)?

It is simply not possible to produce Amarone wine for pennies. There are a number of purely technical reasons why it costs more to produce Amarone della Valpolicella than wines made by pressing and fermenting fresh grapes.

The grape selection

Grapes for air-drying are always harvested by hand, because their skins must remain intact. Otherwise, grapes will rot during the long drying process. Naturally, hand-harvesting is more expensive than machine-harvesting. The disciplinare demands that the winemaker pick only 65% of their best grapes for the Amarone. This means that not as much wine can be produced.

The complex winemaking process

Secondly, the appassimento method is very demanding. The drying process takes 3-4 months, and occupies valuable space in the winery. The process involves the use of shelves and industrial fans, which run 24×7 and use up electricity.

As fresh grapes are air-dried in fruttaio, water evaporates and they lose about 40% of their mass. When the resulting half-raisined grapes are pressed, they produce much less juice, and much less free-run wine (vino fiore).

The long ageing processes

The third factor is the long ageing time. According to the disciplinare, the required ageing time for Amarone is two years, increasing to four years for Amarone Riserva. But that’s the bare minimum. Serious wineries undertake a longer ageing regimen. To mature their Amarone wine (especially Riservas) to perfection, 5–7 years is not unusual. For example, in 2023, such wineries will be releasing their 2016–2018 vintages.

Conclusion: what you should expect to pay for Amarone della Valpolicella

The cost of buildings, electricity and labour stack up. For purely technical reasons, this needs to be covered by wine sales. As a result, Amarone costs more than easy-to-produce mass-market wines. In addition, the price of the best Amarone wines is determined by the prestige and the reputation of the winery, and if it has received prestigious wine awards.

So, what is the expected price for a bottle of Amarone? It is not surprising that Amarone della Valpolicella wine from a good vintage, aged for 5–7 years, will sell for around £40-60 per bottle.

The asking price for a collectible, award-winning bottle of Amarone, typically exceeds £100.

Here are a few examples of award-winning Amarone della Valpolicella, to give you an idea of the price range and variation:

What are the best Amarone vintages

2019 – 4 stars (estimated)

The spring started out warm and dry. But April and May turned out to be the coldest and wettest in the last 30 years. This was followed by a very hot summer, with temperatures peaking at 38°C in June. However, the water reserves accumulated in spring helped the vines to withstand the heat. The end of summer was patchy, with sunshine interrupted by hailstorms.

2018 – 4 stars

Spring was patchy, with periods of warm weather interrupted by cold rainy spells. But it led into a wonderfully sunny and warm summer, allowing the grapes to develop all of the important chemical building blocks needed for deep colours and flavours. Early September was sunny and warm, allowing the grapes to finish ripening and leading to a good harvest.

2017 – 3 stars

This was a warm and dry year, with harvest starting about 10 days earlier than normal. In early September, just before harvest, quite a few vineyards in Valpantena and Eastern Valpolicella were hit by hailstorms.

2016 – 5 stars

This year, the grapes followed their historic schedule of maturation and ripening almost perfectly. To be fair, the season saw quite a bit of rain, with July and August being quite cool. But the end of summer was followed by a gorgeous autumn, and the harvest started right on time.

2015 – 4 stars

Despite some challenges, 2015 was a fine vintage. It began with quite a bit of rain at the start of the season – well above average. However, starting from late April, the weather became warmer and drier than normal. This accelerated the ripening and the harvest time, but only by a few days.

2014 – 2 stars

2014 will be remembered as the rainy year. Spring started really well, without any frost. But the rest of the season was an uphill battle. The summer was very rainy, with July setting the historic record. Due to cloud cover, it was colder too. The dry and sunny September was a welcome change, and growers delayed the harvest to compensate for the tough summer.

2013 – 4 stars

This year had a cool and rainy start followed by a perfect second half of the season. Rain, and a spell of cool weather, lasted until May. But the sunny and dry summer months were perfect. August and September had marked day-night temperature swings, which is always beneficial and helps grapes to develop more complex aromas.

2012 – 3 stars

This was quite a hot year, and at times emergency irrigation had to be used. The end of spring was cold and rainy, but the summer was very warm with little rain. As a result, vines sustained a lot of stress. Things got back to normal near the end of the season, leading to a good harvest.

2011 – 4 stars

The warm and dry spring weather was interrupted by rains that prevailed until July. But with August and September being sunny, warm and dry, the grapes matured well and were picked a bit earlier than usual.

2010 – 4 stars

This was a cool and rainy season until the weather finally changed in August. The dry spell lasted well into September. Although the harvest was ten days late, the grapes ultimately matured well.

The terroirs of Valpolicella and how they influence taste

The river Adige forms the western border of Valpolicella, flowing about 6km east from Lake Garda. The eastern border is the province of Vicenza. The Lessini mountains, which form a part of the Venetian Prealps, are the northern boundary. In the south, Valpolicella touches the suburbs of the historical city of Verona.

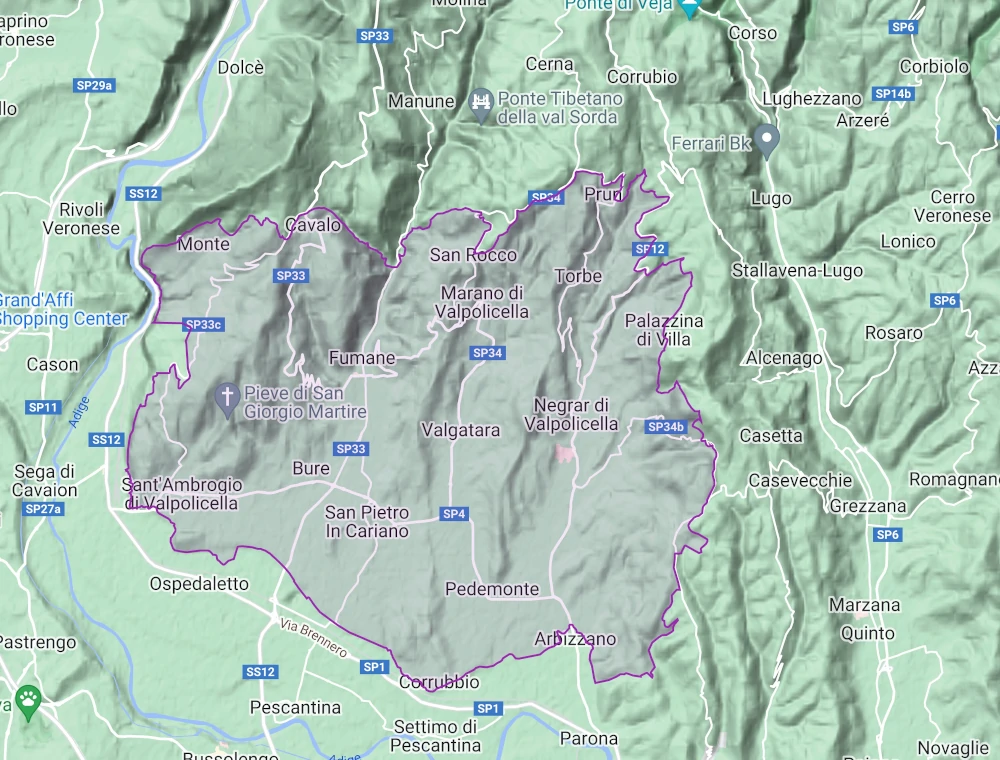

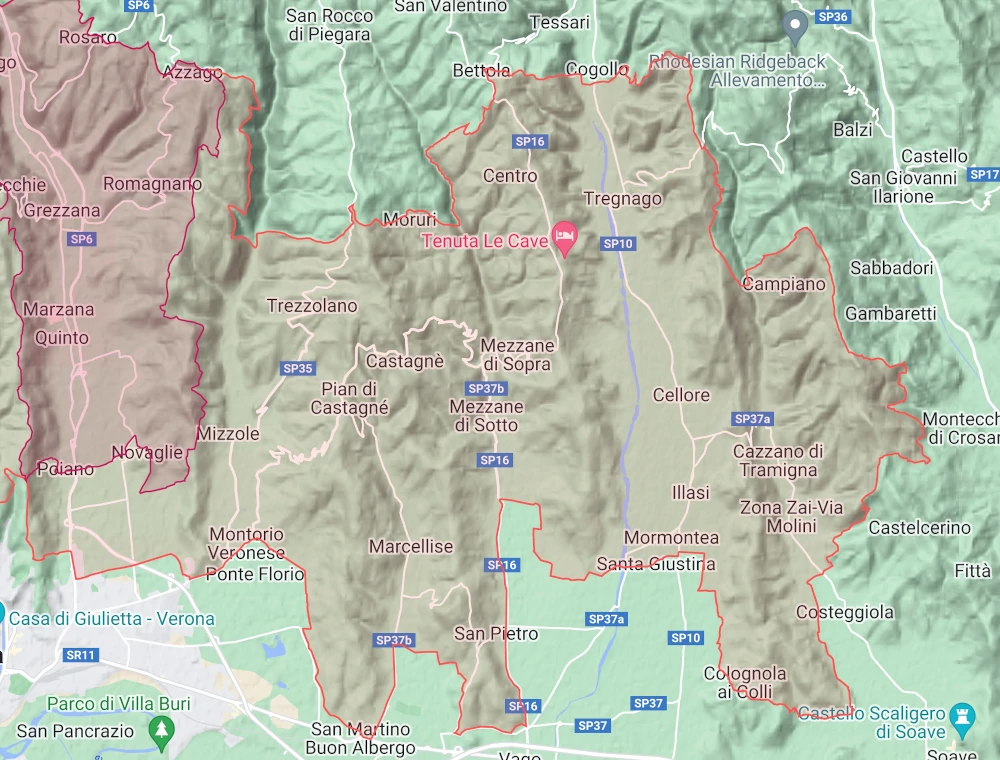

The growing area of Valpolicella consists of three sub-zones. The Valpolicella Classico zone is in the west, near Lake Garda. This is the traditional zone for Valpolicella wines. In 1968, it was expanded to include two more zones: the valley of the Valpantena river, and Valpolicella Orientale – or Eastern Valpolicella. Each sub-zone is further divided into valleys.

The terroirs of Valpolicella are very diverse, and each contributes a unique flavour to its wine. For example the foothills of the Lessini mountains are based on limestone-dolomite formations. The soils here are mostly sedimentary in nature. They’re rich in limestone and calcium carbonate, and produce bold wines with structure, body, and remarkable longevity. The area is known to have volcanic soils, which are associated with very complex flavours [5]. Soils in the flatlands of Valpolicella, closer to the city of Verona, contain mostly gravel, clay and sand. They produce wines of lighter colour with fruity fragrant flavours.

Valpolicella Classico and the influence of Lake Garda

Classico is the traditional area of Valpolicella, where this wine was born. The climate is cooled by the Adige river and Lake Garda in the west, as well as the Lessini mountains in the north.

Because of the influence of Lake Garda, the climate in the Classico area is milder than in the rest of Valpolicella. In summer, Lake Garda produces cooling breezes. But in winter, the water remains warmer and thus keeps air in the vicinity warmer too.

The slopes of the Lessini mountains are south-facing, which helps the grapes to absorb more solar energy and ripen well. As a result of these influences, the wines in the Classico zone typically have a rich, bold, and supple style. They are more tannic, with a fuller body and higher alcohol levels.

Having said that, at higher altitudes the air is colder and ripening is slower. Vineyards planted in Sant’Ambrogio di Valpolicella (up to 650 metres), or Valle di Negrar (300-400 metres), show a more elegant and austere character.

Valpantena: the breezy valley

This valley occupies the central part of Valpolicella, following the Prodno di Valpantena stream. The climate here is colder than the rest of Valpolicella because it is cooled by chilly breezes from the Alps. Most of the vineyards are planted at lower altitudes than in the Classico area, near Romagnano and Santa Maria di Stelle.

Since the Valpantena stream runs from north to south, the vineyards have an eastern and western exposure. As a result, grapes take longer to ripen so the harvest in Valpantena takes place later than in the Classico area. The wines of Valpantena are more elegant and fresh, with higher acidity, and good longevity.

Valpolicella Orientale

Valpolicella Orientale (or Eastern Valpolicella) has some of the newest and most innovative wineries. Many vineyards are planted at altitudes ranging from 100 to 500 metres in the foothills of the Venetian Prealps. Climate in the area is influenced by cooling winds from the mountains, lengthening the ripening time at higher altitudes. Soils on the hillsides are rocky and less fertile.

Massimago is a remarkable example of innovative winery from the area. They were among the first to produce organic Amarone (it’s hard to dry grapes without chemicals following the organic rules). To make winemaking closer to the public, they introduced “winemaking experiences”: regular customers were invited to help with harvesting and to press the grapes like in the old days – with their bare feet !

The most important parts of Valpolicella Orientale are Valle di Mezzane and Valle d’Illasi. Wines from these zones are fruity and elegant, complicated by herbal notes.

Valpolicella and Amarone grapes and “The Valpolicella Formula”

The “new” Valpolicella formula

The so-called “Valpolicella formula” is defined in the wine laws of Amarone, Valpolicella and Recioto (and shared between them). Wines must be made from a blend of Corvina Veronese (45–90%) and Rondinella (5%–30%). Corvinone can replace Corvina for up to 50% of the blend.

In addition to that, up to 25% of the blend can be made up of other grapes permitted in the province of Verona. These should make up no more than 10% per grape variety [1, 2, 3, 4].

The “old” formula

Until 2003, the Valpolicella formula was different. It included Corvina Veronese, Rondinella and Molinara. But in 2003 Molinara was taken off the list.

It is yet another controversial topic in Valpolicella. Some producers consider Molinara a lesser-quality grape. Others believe it is a highly important element of the blend, adding elegance and helping to balance the powerful Amarone wine.

In practical terms, even today many wines are produced with a small addition of Molinara. Other wineries choose to add both Molinara and Oseleta, or only Oseleta. The truth is, while Molinara is not mandatory anymore, it’s too early to write it off.

Permitted Valpolicella grapes

Corvina Veronese

Corvina Veronese – also known as Corvina or Cruina – is the most important grape that defines Valpolicella. It produces ruby-red wines with a medium-deep colour, and flavours of strawberry, raspberry and rose, as well as nutmeg, cinnamon and cloves. It’s not a very tannic grape, and winemakers typically add other permitted grapes to build up the desired body of their wine.

The notable red fruit aromas of Corvina are produced by naturally occurring red-berry chemicals. The first one is furaneol (also known as strawberry furanone). It is also present in strawberries and pineapple, and is often used to make perfumes. Another notable chemical is β-damascenone, which is the main aroma of rose (and of Kentucky bourbon), and ethyl cinnamate (aroma of cinnamon).

Red fruit flavours have become the signature of Valpolicella, so it’s no wonder regulations for Valpolicella DOC, Valpolicella Ripasso DOC and Amarone della Valpolicella DOCG allow Corvina to make up to 90% of the blend.

Though it’s possible to find wines made mostly of Corvina, in practice you tend to see Amarone and Valpolicella wines made up of about 40-60% Corvina. Amarone seems to need more sugar, which is added by Rondinella, and more body, which is supplied by Corvinone.

Esteemed wine writer Ian D’Agata writes that the most important feature of Corvina is that it responds well to drying [5]. This characteristic sets it aside from other red grapes. For example, dried Merlot and Cabernet Sauvignon tend to develop unpleasant aromas when dried.

Again, it makes sense to use Corvina for Amarone wine. After the harvest, grapes are stored in the wineries and lightly dried to concentrate the acid, sugar and flavour. This results in wines with a much richer taste.

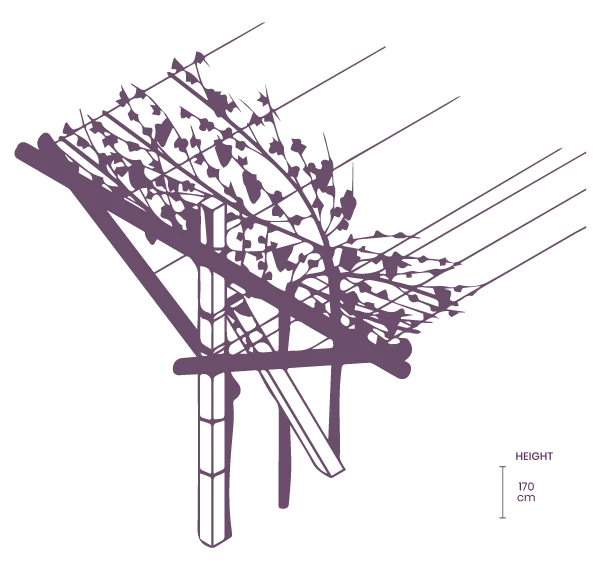

Corvina is a finicky grape, and can easily by affected by fungus. Because of that, Corvina vines are typically trained to the Pergola Veronese system. Traditional to this area (as the name suggests), the pergola system has vines growing on an overhead trellis (pictured ). This allows as much air circulation as possible.

Corvina is not just grown in Valpolicella, but in other parts of Italy too. Overall, it is planted on over 7.5 thousand hectares. This area has doubled since 1970 [6].

Corvinone

Despite the similar-sounding name, the grape Corvinone is not a DNA relative of Corvina. In fact, it’s been shown to be a distinct varietal [5]. Both the berries and the bunches of Corvinone are larger than those of Corvina – that’s why the name of this grape vaguely translates as “big raven”.

The berries of Corvinone are bigger than those of Corvina, and they are more widely spaced in a bunch. This grape has thicker skin, and produces more tannic, deeper-coloured wines. But most importantly, the thick skin makes it even better suited for appasimento – the process of drying and concentrating flavours.

Wine laws permit winemakers to use Corvinone to replace up to 50% of Corvina in a blend. Nicola Scienza, the winemaker at Rubinelli Vajol, says:

“Corvinone gives more finesse than Corvina. It has less alcohol and more marked acidity than Corvina, and a more intense and broad spectrum of olfactory sensations.”

So, each winemaker will choose how much Corvinone to add to the blend depending on the style they want to create.

While Corvinone can replace up to 50% of Corvina, in reality it’s a much less planted grape. Only one thousand hectares are grown, less than a seventh of the vineyard area dedicated to Corvina [6].

Rondinella

Rondinella is used to make up 5% to 30% of a Valpolicella blend. Rondinella adds complexity to the wine, as it has a fruity and multifaceted bouquet with notes of ripe red fruits, cherries, tobacco, and spices. This grape also turns the colour of the wine a tone darker, lending a vivid ruby or purple undertone.

But perhaps the biggest reason for adding Rondinella to the mix is that it accumulates sugars better than Corvina and Corvinone. So this grape is very important for wines that need higher alcoholic strength like Valpolicella Ripasso and Amarone, or in the sweet wine Recioto della Valpolicella.

While Rondinella is an important player in Valpolicella, it’s also widely used in Bardolino DOC and Bardolino Superiore DOCG. These regions lie to the west, between the river Adige and Lake Garda. Over 2.5 thousand hectares of Rondinella are planted across Italy [6].

Molinara

This big, juicy grape develops wines with elegant tastes of red berries, flowers and a hint of salt. Nicola Scienza says “In our province, Molinara is also called “Ua Salà”, which means “salted grapes” for its marked savoury notes.”

On its own, Molinara produces light-coloured, low-alcohol wines with fragrant flavours of wild red berries. It is thought to be even better suited to rosé wines.

Unfortunately, as it possesses such a fragrant nature, Molinara fell out of favour in the 1990’s when deep, dark styles of Merlot and Cabernet became so popular [5].

So while Molinara can make up to 10% of the Valpolicella blend, it is not always added. For many wineries Molinara has become a thing of the past. The plantings of this grape have shrunk from over two thousand hectares in the 1970’s to less than six hundred hectares today. Unfortunately, this trend shows no sign of reversing [6]. But some successful winemakers (such as Rubinelli Vajol) think it adds complexity to their wines, and use it as the special ingredient in their formula.

Oseleta

Its name comes from “osei”, which means “birds” in the Veronese dialect, as Oseleta is very popular with birds. This grape has dark skin. It’s remarkably tannic and bursts with flavours of blueberries, black cherry, minerals and aromatic herbs.

Bunches are small, stocky, tight and have tiny berries, suitable for producing extraordinarily concentrated wine. Wines with Oseleta in the blend are deeper, darker, fuller-bodied, spicy and tannic.

This grape is optional and is only used if the winemaker wants to add these qualities to their wine. Even adding a small quantity of Oseleta can have a big effect, making the wine deeper and more tannic. Because of that, only a few winemakers use it. Even for them, Oseleta makes up only 5-10% of the total blend. Only 15 hectares of this grape are planted in Valpolicella, so it’s quite rare and tends to only be found in premium wines.

Vine training: Pergola Veronese and Guyot

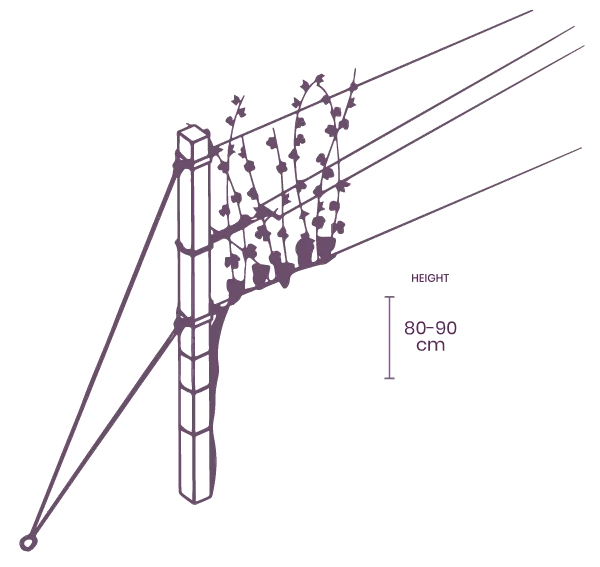

Our story about Valpolicella grapes would not be complete without explaining the traditional vine-growing techniques. The official wine-making standards (disciplinare di produzione) in Valpolicella strictly forbid using any other vine training methods than Pergola Veronese and Guyot (which is a French term; in Italy it’s called Spalliera).

Pergola Veronese is a traditional system, where shoots are attached to trellises that run horizontally. The main advantage is that the canopy is lifted quite high, to about 1.7 metres above the ground. Here’s a schematic picture of pergola from the Consorzio’s website, and also a photo I’ve taken in a vineyard in Valpolicella.

The Guyot system means the vine’s shoots are tied to trellises that run horizontally. So the vine grows upwards, making grape bunches easily accessible during harvest.

Both Pergola and Guyot have about the same leaf surface area per hectare. The most important thing to consider when choosing either Guyot or Pergola is that each creates growing environments with different microclimates.

Benefits and limitations of the Pergola Veronese system in Valpolicella

Nicola Scienza of Rubinelli Vajol explains the advantage of Pergola:

“When it rains during the harvest the grapes dry out much earlier. Pergola also offers the advantage of protecting the grapes from direct solar radiation. This is one of the problems many winegrowers face in the frequent heat waves that have occurred over the latest years.”

Because of the rooftop position of the canopy, Pergola exposes its leaves to a greater level of solar radiation, which facilitates vine’s growth. At the same time, berries are shaded. This protects them from damaging sunburn and also keeps their temperature cooler. But as a consequence, Pergola produces berries with thinner and less pigmented skins – resulting in a lighter colour of the final wine.

The Pergola results in slightly more fertile vines than Guyot, so it produces more grape bunches per unit area. It’s more suited for vigorous vines, in areas with high availability of water.

Benefits and limitations of the Guyot system in Valpolicella

Guyot exposes both the leaves and berries to the sun, which helps during ripening. This technique is perfectly suited to control the overgrowth of canopy to stop the leaves from taking precious nutrients from the grapes. But it requires careful canopy management, as some leaf cover is required to protect the grapes from the sun.

Both systems – Pergola and Guyot – are used quite extensively in Valpolicella. One system is not “better” than the other, as they both have benefits and limitations. So, like the blend of grapes, winemakers have to pick and choose what’s best for their particular site.

References

[1] Disciplinare di produzione dei vini a denominazione di origine controllata e garantita “Amarone Della Valpolicella” Modificato Con DM 07.03.2014, MiPAAF

[2] Disciplinare di produzione dei vini a denominazione di origine controllata “Valpolicella”, Modificato Con DM 07.03.2014, MiPAAF

[3] Disciplinare di produzione dei vini a denominazione di origine controllata “Valpolicella Ripasso”, Modificato Con DM 07.03.2014, MiPAAF

[4] Disciplinare di produzione dei vini a denominazione di origine controllata e garantita “Recioto Della Valpolicella” Modificato Con DM 07.03.2014, MiPAAF

[5] Ian D’Agata, Italys Native Wine Grape Terroirs, University of California Press, 2019

[6] Catalogo Nazionale delle Vatietà di Vite, MiPAAF

[7] https://www.quattrocalici.it/denominazioni/valpolicella-doc/

[8] Le ricerche di Stefano De Stefani sui Lessini. La vicenda umana dalle memorie famigliari. Annuario Storico della Valpolicella, V.18

[9] «Il vostro amico preistorico». La corrispondenza fra Gaetano Chierici e Stefano De Stefani, Annuario Storico della Valpolicella, V.18

[10] Conzorzio Valpolicella https://www.consorziovalpolicella.it/en/